Click here to listen to the album whilst you read

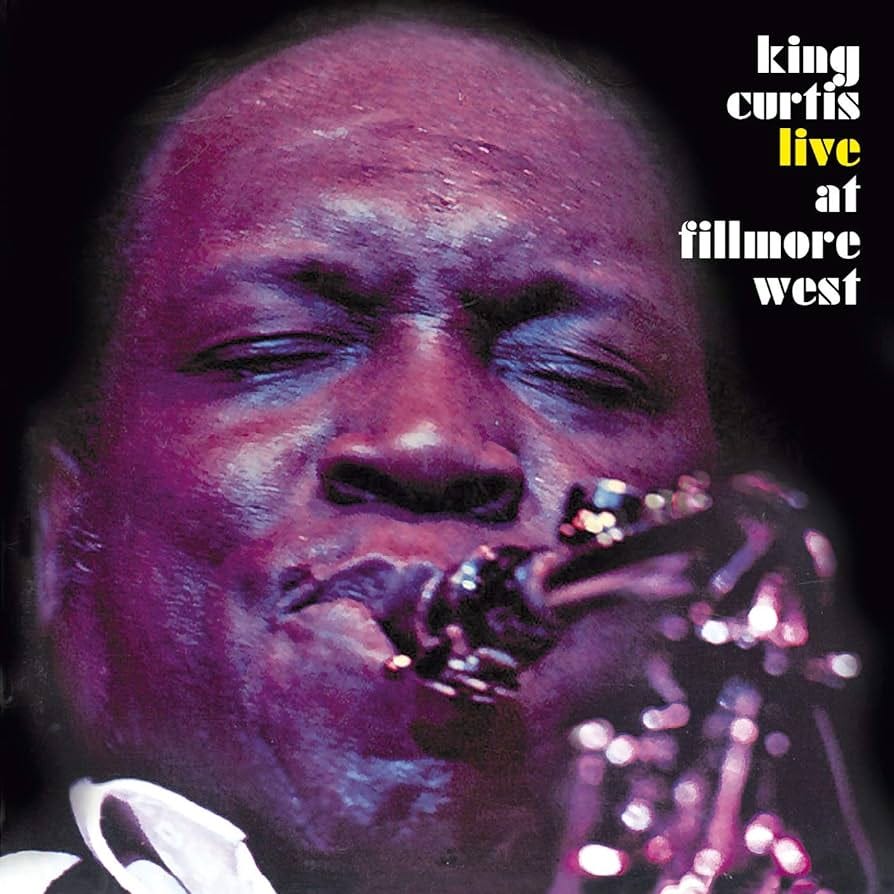

Whilst I was certainly aware of the incredible Memphis Soul Stew, which a friend had turned me on to in my late teens, King Curtis’s “Live At The Filmore West” was something I discovered, like most British people I suspect, via the film Withnail & I.

Those familiar with the film will doubtless recall the opening scene, in which the live rendition of “Whiter Shade of Pale” by Curtis matches some divine scene-setting in arguably one of the UK’s funniest comedies:

That cover version had me hunting for the track, and the obvious route was to acquire the soundtrack to the film. In a wonderfully ironic twist though, that soundtrack was - and remains, on vinyl anyway - incredibly hard to find.

As a consequence, I take the view that a lot of people wound up buying Live At the Fillmore West purely to get hold of that performance of Whiter Shade of Pale.

I was no exception, hunting it down and - initially - buying it purely for that one song.

Of course, the reality of what is a most treasured album for me now, is that one might even argue that Whiter Shade of Pale is one of the weaker songs on the album, such is the brilliance of the set.

By the time Live… was released, King Curtis had cut quite the career already, carving out a space as the go-to session player. His is the horn you hear on The Coasters’ Yakety Yak, but he also sessioned for Buddy Holly, co-writing and playing on Reminiscing. The Kingpins even opened for The Beatles at Shea Stadium, and Curtis would later provide sax for John Lennon, on It’s So Hard and I Don’t Want To Be A Soldier in Feb 1971 - songs that tragically would prove to be among Curtis’s last performances:

By March ‘71 when Live At The Fillmore West was recorded then, Curtis had very much cemented his position as the go-to sax man who could comfortably straddle soul, jazz, rock and more.

The album was actually recorded over three nights, where King Curtis and his Kingpins were the backing band for Aretha Franklin, who was the headline event and for whom Curtis had played since around 1967. She too released an album of the show - Aretha Live At The Fillmore West.

The Kingpins warrant a mention here, as they were undoubtedly some of the finest players on the circuit: Billy Preston on Hammond organ, Bernard Purdie on drums, Jerry Jemmot on bass and Cornell Dupree on guitar. I suspect separate, lengthy essays could be written about all four, such is their own standing in the world of music. “Tight” doesn’t even start to cover it in terms of the way this group played; the cohesion was ridiculous.

The rendering of Memphis Soul Stew sets the tone, with all players delivering tight, funky turns that certainly lets everyone - us included - know that they didn’t come to mess around. Purdie warrants a special mention for his drum turn in my view though, delivering a perfect, powerful showcase of funky drumming, as ever.

The mood then takes a step down, with the aforementioned cover of Whiter Shade of Pale. For me the original by Procul Harum was solid enough, but compared to the lyrical sax delivery here, it almost feels like a dirge. Curtis’s whole style was loose and almost playful, and there’s perhaps no better example than what he delivers here; a soulful exploration that finds new depths in the song's melancholic melody. It's a testament to his genius that he could take a song so distinct and imprint upon it something so uniquely his own.

For me it is inherently connected in my mind’s eye to that scene above, but frankly it also became a soundtrack of choice to many a hard-woken morning where a hangover was lingering in the background, you were dog tired and you knew full-well that the bulk of the day was a write-off, condemned to the sofa with any comfort food you could find and some kind of easy watch on the TV.

If Whiter was an odd choice of a sort, what follows it is an even more explicit statement of intent: another cover, this time of Led Zeppelin’s Whole Lotta Love. Unlike Whiter Shade of Pale, I’d argue this one does not trump the original, but it does nonetheless deliver a powerful, funky take, with Purdie again proving the rhythmical core, propelling the energy along.

From uptempo to down once more, as the mood switches back with the cover of I Stand Accused, which sees Curtis deploy a wah-wah pedal on his sax licks, something I’d certainly never heard before when first listening. The mood is powerful, almost quietly angry, both in the way Curtis delivers a monologue mid-song, but also in the way he blows his sax. Before letting loose he talks about having “something I been carryin’ around, I just wanna get off my chest, tell you how I really feel about it”, and my god it shows. Again, the emotion pouring through here is powerful, soulful and undeniable.

After that moment of sheer emotional weight, it feels fitting that what follows is the lighter, funkier Them Changes. After what has gone before it almost feels like a moment of levity, just releasing that tension with something more frivolous. I wouldn’t say it’s one of the better tracks on this album, but even if it was the worst, it would still be leagues above most.

Ode To Billy Joe feels like another downtempo moment, again just controlling the mood and flow of this performance. Keeps your ears on Bernard Purdie though, who once again delivers some of the tightest, most casually funky drumming you’ll ever hear. The effortlessness of it is almost irritating; if I was a drummer it would drive me mad hearing someone play with such fluidity and control whilst making it sound about as taxing as putting the kettle on.

What follows next is, for me anyway, the highlight of the album: Curtis’s cover of Mr Bojangles. Nina Simone’s rendering of this classic was moving, stirring and powerful. It set an absurdly high bar; one of those tracks where any thought of covering it should come with a serious warning to re-think before proceeding.

Under Curtis’s control though, Bojangles seems to contain a simultaneous whimsy and weight. Cornel Dupree’s guitar doubtless plays a strong part here, with that light, airy melody he plays out. But soaring over that, at times casual and easy, at other times weighty and dripping in emotion, is Curtis’s sax. Billy Preston warrants a mention too, underpinning the song on the Hammond, again allowing that space for Curtis to drift freely, delivering his own version of a vocal that somehow manages to set this song into a whole other space from the original. For me, it is a highly emotional performance somehow delivered in this breezy manner - a juxtaposition I still remain in awe of. That’s near-impossible to pull off in my view, and yet Curtis does so here.

After that quietly powerful moment, it is a brief diversion into uptempo fun in the albums penultimate song, Signed Sealed Delivered. It almost acts as another moment of levity to avoid the mood turning too introspective after Bonjangles.

In that regard, the set list here is a masterpiece of pacing for an album. Just when the songs ratchet up in tempo, they then come back down, only to pace up again. It’s a wonderful trip.

The final song on the album is Soul Serenade, another slightly moody piece that was one of Curtis’s best-known songs. It has a lazy kind of swagger, showing that kind of relaxed level of cool that the Kingpins exuded, seemingly without too much effort. As a send off, it’s a bold one, not looking to go out with a bang, but to instead comfortably bring matters to a close, before exiting stage left.

As an album, Live At the Fillmore West would ultimately have a bittersweet ending, in particular with that final song, Soul Serenade. In August 1971, just fives months after these performances, Curtis was murdered outside his brownstone in New York City. Apparently he was trying to access a fusebox outside his house, the way to which was being blocked by a drug addict who refused to move. A confrontation ensued, during which Curtis was stabbed, dying in hospital the following morning from his injuries.

At Curtis’s funeral, the Kingpins played Soul Serenade. Robbed of its sax contribution, I’d imagine that must have been a haunting listen. In attendance were the likes of Aretha Franklin and Duane Allman, among others.

That epilogue certainly casts a shadow of sorts over this album, but to me, there’s just so much to love too. You have those moments of uptempo musicianship, but you also have, in the likes of Bojangles and Accused, phenomenally emotional, moving moments, the likes of which are few and far between.

I rarely hear this record get mentioned, but to me it’s an essential purchase; one for the ages. The pure joy you can get from it is undeniable, and it remains one of my go-to Sunday morning type of records. It may be the Withnail influence, but it’s that album to just play when you want to ease into a day with some bright, brilliant, soulful sounds. It touches me every time.

RIP King Curtis x

Off to a great start! A fine recording I’ve enjoyed for decades that’s been released not only with extra tracks (incl. “My Sweet Lord”), but also paired with Aretha’s release in a four-disc set.

As for your intro: I was pleasantly surprised by your approach after reading this first review, because I wanted to wait to see how much the reviews might fall into that standard state that has that same empty feeling that you get when someone starts describing the dream they had last night. “… oh, that record was so important to me and my, soon-to-be, wife …” - that kind of thing.

In this case, it doesn’t even matter if you’ve ever cared for - or even heard of - “Withnail & I”, the connect is not all that important when it comes to this recording, yet you’re able to create interest in the album. Thanks again. Very enjoyable.

Fine album, glowing mentioned in recently released Bosch Legacy series 2. Right up there with Donny Hathaway Live!